A web site full of stuff that should be useful

| AS Psychology |

| Core Studies |

| Links |

| Course Content |

| Exam Questions |

| Psychological Investigation |

| Themes and Perspectives |

| Glossary |

| About this site |

| Stuff |

| For Teachers |

|

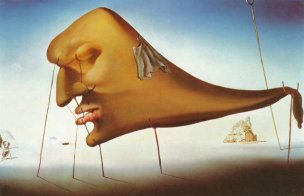

Dali (1937) Sleep

|

![]()

Dement, W. & Kleitman, N. (1957).

The Relation of Eye Movements During Sleep to Dream Activity: An Objective Method for the Study of Dreaming.

Background It

is possible to see at times the eyes of a sleeping person moving. These periods of prolonged rapid eye movements (REM) were

thought by Dement and Kleitman to have some connection with

dreaming. It

seems that all humans dream but dreams are easily forgotten. Freud argued that the function of dreaming was to preserve

sleep by unconsciously fulfilling wishes which would otherwise upset

and therefore disturb the sleeper.

Freud therefore argued that dreams are the ‘royal road to

the unconscious’, meaning that dreams allow therapists to have an

insight into their clients’ unconscious thoughts.

More

recently, psychologists have focused on cognitive and physiological

explanations for dreaming. For

example a cognitive approach might explain how dreaming is a way of

dealing with our problems such as those relating to work and

personal life. Whereas a physiological approach might explain

dreaming as the result of random firing of neurones which create an

image which we then put meaning to. During

a typical night a sleeper passes through different levels of sleep

in a cyclic fashion between 5 and 7 times.

Level 1 and 2 are light sleep characterised by irregular EEG

patterns. Level 3 and 4

are deeper levels and are characterised by regular wave patterns.

Stage 4 is called slow wave sleep or deep sleep.

After stage 4 the sleeper goes back up the ‘sleep

staircase’ to stage 2 and there is a period of REM sleep lasting

for about 15 to 20 minutes. These

sleep states alternate during the night starting with a rapid

descent into deep sleep, followed by progressively increased

episodes of lighter sleep and REM sleep. Note that the shaded are are REM sleep Aim

The

aim of the study was

to investigate the relationship between eye movements and dreaming. The study had three hypotheses:

Procedure/Method The

nine participants were seven

adult males and two adult females. Five

were studied intensively, while only a small amount of data was

collected on the other four just to back up the findings of the main

five. The

participants were studied under controlled laboratory conditions,

whereby they reported to the laboratory just before their usual

bedtime. They had been

asked to eat normally but to avoid caffeine or alcohol on the day of

the study. The

participants went to bed in a quiet, dark room. An

electroencephalograph

(EEG) was used to amplify and record the signals of electrodes which

were attached to the participants face and scalp.

Two or more electrodes were attached near to the

participants’ eyes to record electrical changes caused by eye

movement. Two or

three further electrodes were attached to the scalp to record brain

activity which indicated the participants’ depth of sleep.

The participants then went to bed in a quiet, dark room.

Testing

Hypothesis 1

(there will be a significant association between REM sleep and dreaming) At

various times during the night (both during REM and N-REM sleep) the

participants were awakened to test their dream recall.

The participants were woken up by a loud doorbell ringing

close to their bed. The

participant then had to speak into a tape recorder near the bed.

They were instructed to first state whether or not they had

been dreaming and then, if they could, to report the content of the

dream. The participants

were only recorded as having dreamed if they were able to relate a

coherent and relatively detailed description of the dream content.

Different participants were woken according to different schedules. Two were woken at random. One was woken three times in REM followed by three times in N-REM and so on. One was woken randomly but was told that he would only be woken during REM. Another was woken at the experimenter’s whim. In an attempt to eliminate the possibility of experimenter effects, the experimenter did not communicate with the participants during the night. Furthermore to help prevent bias the participants were never told, after wakening, whether their eyes had been moving or not.

Testing

Hypothesis 2

(there will be a significant positive correlation between the estimate of the

duration of dreams and the length of eye-movement) The participants were also woken up either five minutes or fifteen minutes into a REM period, and asked to say whether they thought they had been dreaming for five or fifteen minutes.

Testing

Hypothesis 3

(there will be a significant association between the pattern of eye movement and

the context of the dream) The participants were woken up as soon as one of four patterns of eye movement had lasted for at least one minute. On waking, the participant was asked to describe in detail the content of their dream. The four patterns that prompted an awakening were: (a) mainly vertical eye movements; (b) mainly horizontal eye movements; (c) both vertical and horizontal eye movements; (d)

very little or no eye movement.

Results/Findings

All

the participants showed periods of REM every night during sleep. The REM EEG was characterised by a low voltage, relatively

fast pattern. In

between REM periods the EEG patterns were either high-voltage, slow

activity or spindles with a low-voltage background, both

characteristic of deeper sleep.

REM never occurred at the beginning of the sleep cycle REM

periods which were not terminated by an awakening varied between 3

minutes and 50 minutes with a mean of about 20 minutes, and they

tended to increase in length as the night progressed.

The REM periods occurred at regular intervals during the

night, though each participant has their own pattern:

the mean period between each REM phase for the whole group

was 92 minutes, with individual norms varying between 70 minutes and

104 minutes. Results relating to hypothesis 1 (there will be a significant association between REM sleep and dreaming) Table showing the incidences of dream recall after awakenings during periods of REMs or periods of NREMS

The

results show that REM sleep is predominantly, though not

exclusively, associated with dreaming, and N-REM sleep is associated

with periods of non-dreaming sleep. Nearly

all dream recall in N-REM awakenings occurred within eight minutes

of an REM, suggesting that the dream might have been remembered from

the previous REM Results

relating to hypothesis 2

(there will be a significant positive correlation between the estimate of the

duration of dreams and the length of eye-movement) Results

of dream-duration estimates after 5 or 15 minutes of rapid eye

movements

Estimates (in minutes) Estimates (in minutes) after 5 minutes REM after 15 minutes REM

Subject Right Wrong Right Wrong

DN 8 2 5 5 IR 11 1 7 3 KC 7 0 12 1 WD 13 1 15 1 PM 6 2 8 3

Total 45 6 47 13

The series of awakenings which were carried out to see if the participants could accurately estimate the length of their dreams, revealed that all the participants were able to choose the correct dream duration fairly accurately, except for one participant who could only recall the latter part of the dream and so underestimated its length. Results relating to hypothesis 3 (there will be a significant association between the pattern of eye movement and the context of the dream) There

did appear to be some relationship between the dream content and the

type of eye movements. Periods

of pure vertical or horizontal eye movements were rare, but when the

participant was woken up after a series of vertical

eye movements they reported dreams such as: Ø

standing at the

bottom of a cliff operating a hoist, and looking up at the climbers,

and down at the hoist machinery. Ø climbing up a series of ladders looking up and down as he climbed. Ø throwing basketballs at a net, first shooting and looking up at the net, and then looking down to pick another ball off the floor. In

the only instance of horizontal

eye movements, the dreamer was watching two people throwing

tomatoes at each other. In

the 21 awakenings after a mixture of eye movements, participants

were always looking at people or objects close to them (e.g.

talking to a group of people, looking for something, fighting with

someone), there was no recall of distant or vertical activity. In

the 10 instances where the participants showed little or no eye

movements, the dreams involved the dreamer watching something at a

distance or just staring fixedly at some object. In

order to confirm the meaningfulness of these relationships, 20 naive

participants and 5 of the experimental participants were asked to

observe distant and close-up activity while awake.

These measurements were in all cases comparable to those

occurring during dreaming. Evaluation of Procedure An obvious weakness of the

study is its lack of ecological validity.

The situation in which the participants had to sleep was

unusual and could have affected their sleep patterns.

Also the nature of the method of waking participants may have

affected their ability to recall their dream.

A

further problem with the study was the sample size.

The sample size was small and only included 2 females so we

could argue that the results were biased towards the dream pattern

of men rather than women.

Subsequent studies have found that there are large

differences between individuals in the reports of dreaming during

REM. Subsequent

studies have not supported Dement and Kleitman’s findings that

there is a relationship between eye movements and what the person is

dreaming about. However

the method was very tightly controlled.

For example the researchers were able to control the

location, sleeping time and the participants use of stimulants.

Reference Dement, W. & Kleitman, N. (1957) The relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: An objective method for the study of dreaming. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 53, 339-46

GROSS, R. (1999) Key Studies in Psychology, 3rd Edition. London: Hodder and Stoughton BANYARD, P. AND GRAYSON, A. (2000) Introducing Psychological Research; Seventy Studies that Shape Psychology, 2nd Edition. London: Macmillan

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||